Amanda Berry, an MFA graduate student at Kendall College of Art and Design in Michigan, is researching “space” as a visual knowledge field. She asked some great questions to the Aesthetics & Astronomy project, which Jeffrey Smith kindly answered. We thought you might enjoy the read:

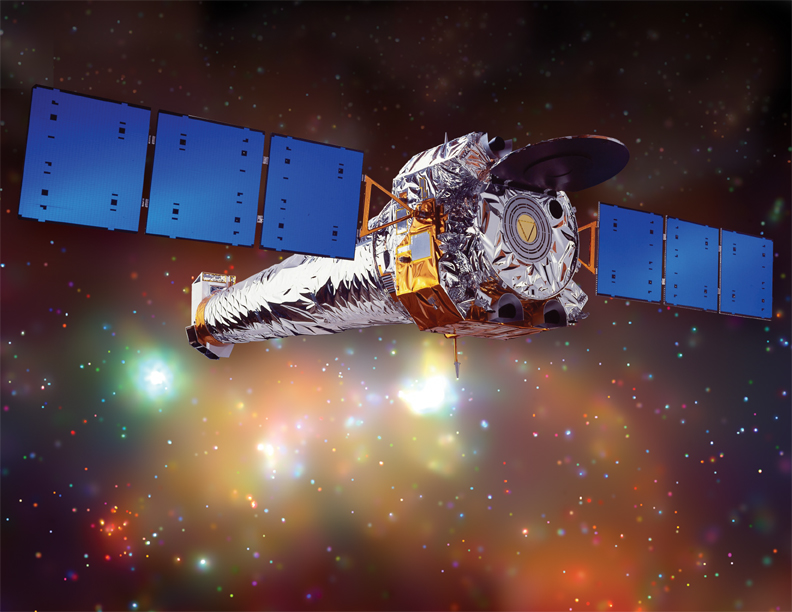

Pushing the very boundaries of observation with new tools and innovation, technology allows us to see father and father into the unknown. Hauntingly beautiful, what can we learn from the images of the universe?

Technology does indeed allow us to see farther than we ever have before. And what we see is indeed stunning. But what do we learn? Well, one of the things we have discovered in our research is that it very much depends on who you are, and to a lesser degree, what kinds of information are provided to support that viewing. We have been using tools from the psychology of aesthetics to look at how regular people (like you and me) look at space images, and we have compared that to what astrophysicists see in them. You can read about this in some of our articles (which is probably how you found our group in the first place), but to summarize quickly, the general public starts with awe, and works their way toward trying to understand just what it is they are looking at. Astrophysicists kind of work the other way around. Those images are basically “data” to them. They interpret them the way a radiologist would look at an x-ray. What am I looking at? What was the purpose of producing the work in this fashion? What did the maker of the work want to highlight here? And if you ask an astrophysicist what is particularly interesting or important in a work he/she might point to something you didn’t even notice was there!

Is space the next “terra incognita”? What drives us to search out and discover new things?

Well, I would turn to work in evolutionary psychology to answer that question (and that isn’t my field!). But if you look at the history of humankind, you always see people reaching out, trying to find out what is around the next corner, over the next hill, beyond the horizon. Lisa and I live in New Zealand. About 1000 years ago, the Maori people left their island (not sure which one, but could have been Hawaii), in hand-built canoes, and took to the ocean to find new land. They travelled thousands of miles in these canoes to reach New Zealand. No certainty of food or fresh water, no idea what they might find or whom they might find there. And yet, they launched those canoes into the ocean. I think space is our frontier, but we explore it in different ways than other explorations.

The furthest reaches of our dreams, the most unimaginable, space lies at the foremost focus of scientists and dreamers, but is the quest for discovery dead?

I think that whenever we hit hard economic times like we are currently experiencing, there is a natural tendency to ask, “What is critical and what is just desirable?” I think we are seeing some of that. But, hard economic times abate, and I think the quest for discovery doesn’t die, it just occasionally gets assigned a lesser priority. It’s a bit hard to think that the last time we went to the moon was 40 years ago!

Phillip Fisher says in his book, Wonder, the Rainbow, and the Aesthetics of Rare Experiences "The experience of wonder no less than that of the sublime makes up part of the aesthetics of rare experiences. Each depends on moment in which we find ourselves struck by effects within nature whose power over us depends on their not being common or everyday." Would images from space fall into this category of wonder and the sublime?

Well, let’s start by defining sublime. Most folks think of the sublime as simply something that is the ultimate in wonderfulness; but that isn’t what sublime means (and perhaps you already know this!). In art, the sublime is something that invokes a sense of awe and wonder that is tinged with fear or terror. There is typically the notion that there is danger lurking. You might see this in a painting where the perspective of the painter must be on a cliff edge or in front of a roaring oceanfront. If you go outside on a very clear moonless night and look at the sky, sometimes it seems overwhelming, and even a bit scary. That is the sublime. I think that space images fall into that category, especially if you seen them projecting very large as in an Imax or planetarium. If, on the other hand, you see them on your iPad, they are still wonderful and intriguing, but maybe slightly less inspiring of awe.

How does our being sighted creatures affect our quest for knowledge of the unknown? What are the limits of human vision and what role does technology play in the visual experience of space?

Very interesting question. Let me start simply. There is an ancient reptile that lives in New Zealand called the tuatara. When it is born, it has a very rudimentary third eye on the top of its head. It can only differentiate light and dark with this eye. The speculation is that this eye lets it spot danger from predator birds flying overhead. Human eyes have developed for human purposes, and looking at the stars really isn’t all that important from an evolutionary perspective. That is, we do navigate from the stars, and determine when to plant crops from the location of constellations, etc., but it isn’t really necessary to see the craters of the moon or the canals on Mars. Compare our eyes to that of a hawk that can see a mouse at a mile, or a possum that can see perfectly clearly at night. But all of that changed with the invention of the telescope, and then again with telescopes sent into space. We combine the data that we get from these telescopes with some creative assignation of colors and intensities to those data, and we find that there is much that we can make sense of and speculate on in space. And then we discover that not only are these images highly informative, they are stunningly beautiful as well.

How is the general public supposed to interpret the images of space? Is there a codex somewhere that would enlighten us as to what the colors mean?

Unfortunately, there is no codex (well maybe in a Dan Brown novel). And that is a big reason why we are conducting the research that we do. We are trying to find out what kinds of information and at what levels people respond to best.

Professor Jeffrey Smith

University of Otago

College of Education